Welcome to another edition of Between Rivers. In this edition we look at the work of John and Marilyn Davies: poetry and a variety of visual art, especially carvings of wild birds.

When I arrived in Prestatyn to meet John and Marilyn Davies it was September, just as in John’s poem Things To Do When The Town’s Closed. Rain and the start of the school term had chased most visitors away, and it was easy to get into the mood of the poem. Like the others quoted here it was first published in his collection Flight Patterns (Seren 1991).

Things To Do When The Town’s Closed

Our choir dressed as guerrilla butlers

has driven the holidaymakers back.

It is September. Seagulls

are critics prying over spilt ink.

The town’s scraped off its silver lining

to get at the cloud instead.

In search of a bit of life,

Ron has started taxidermy, juggling

bags of skin like a homicidal vet.

They grin from furry cells,

near-squirrels.

You can’t keep a good man up.

And Mr. S has emptied his firm’s safe.

Self-bloodied, he faked

assault then described the villain

so well for the police photofit,

like a shout his own face rang out.

On the library wall: ANACKY.

Draughts from the Mersey Tunnel quicken

across the Dee. Wait,

slow down

at the station.

You can find yourself elsewhere.

Balloons were released in August

from Frith Beach for Holiday Fun

with addressed labels. W’s returned

all the way from Builth. His prize?

First cash, soon a court appearance:

winds blew north that day so how come W’s balloon

went south? Well, live in town

and wind is just a ghost. The label went

via his aunt in Builth, both ways by post.

Yesterday, high on a ladder with acres

to paint, Mr. S was whistling ‘Born Free’.

And although the Pleasant Sunday Afternoon Society

now meets all week, although the slipper women

at the launderette seem lively

and waves roll up in fits watching dunes

fail to outwit caravans,

it’s a bad time.

We are alone together.

Even our jeweller’s stopped twinkling.

You can’t help but feel

someone out there might be planning chainsaw

psychiatry or florist pressing.

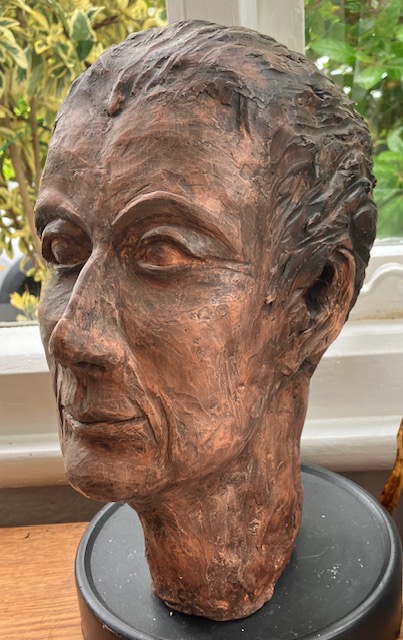

Arriving at the Davies’ home I felt some slight trepidation, having contacted them out of the blue and invited myself round, but they were most welcoming. Marilyn, a small, bright woman, came out to conduct me in, and then here was John, slower, but very thoughtful, and remarkably open in our discussions. I straight away encountered some of Marilyn’s stained glass in the windows. As we ate lunch and discussed some of John’s poems, I started to realise that the house is full of art objects which the couple have created.

I first encountered John’s poems when I was looking for material for Between Rivers, and David Selzer pointed me to A Clwyd Anthology, edited by Dewi Roberts and published by Seren Books. Not all the items in the book were on topic, but one that I knew we had to use was Downing, a Davies poem set in Whitford, near Holywell in Flintshire, on the former estate of Thomas Pennant, the eighteenth-century traveller and natural historian.

Downing

Seventy, rasping, he lives in the saddlery

of the estate now run out of paths.

He keeps the tv. busy. The past? The brisk squire

who toured the eighteenth century and met Voltaire?

Not interested. But around pleasure garden, summer house,

Bob Weston cleared gullies for parched ironworks,

lopped trees in the dingles, was tolerant it seems

of poachers. The house, burned down as an insurance job,

is a DIY kit. Its drive can’t find the gateway.

Tunnels though and waterways built by miners

are intact, theirs or land’s revenge on stateliness

where ponds sag under weed.

Below on Mostyn sands, cockles have been found

by diggers in balaclavas linked to the underground economy.

Jobs, they’re rare as oysters. Unmarked trucks

sidled, and from dunes, they say, the DHSS took photos.

Bob Weston’s watched – Dunkirk again, another

scramble, grab what you can then home, the brass

will know the score. Except the brass aren’t on your side.

Now that it’s wanted for caravans, what no one could visit

is lamented. People will flood in, there’ll be petitions.

But he’ll not be collecting who likes that brandnew

pub at the junction and leaves his dog at home.

I found a copy of his Flight Patterns and was much taken with the vivid characterizations, humour and the sharply cut phrasing. This led me to other volumes of his poetry: The Visitor’s Book (Poetry Wales Press, 1985), Dirt Roads (Seren 1997), and North by South: New and Selected Poems (Seren 2002) which also includes poems from his earlier books, At the Edge of Town (Gomer, 1981) and The Silence in the Park (Poetry Wales Press, 1982). There was also a book of short stories by Welsh authors which he had edited, The Green Bridge (Seren 1988), which introduced me to several unfamiliar voices, notably Caradoc Evans, who unfortunately can in no way be construed as a Between Rivers author. Some of the poems were about belonging or not belonging in small towns on the coast of North Wales or around the Dee estuary. Before our meeting John had already sent me typed notes he had made in 1986 preparatory to the poem Downing. What really struck me was a handwritten marginal note, about the cargoes shipped in via Mostyn Dock on the Dee: bulk phosphate, woodpulp, sulphur, potash. These were not drafts of poetic lines so much as a gathering of ideas and information: to get the poem going, as John said to me. Now over lunch he produced yellowed sheets of typed and annotated historical material about the Flintshire town of Holywell, it’s mythical origins and industrial heyday, out of which he had made the sonnet sequence Burying the Waste. At the time, he said, he thought his poems had to rhyme, and the rhymes helped him to get to the images. Here is the sequence.

Burying The Waste

(Holywell)

Trapped by Caradoc, favourite of a king,

even Winifred could not deny his sword.

Where hair leaked blood, a well of healing

sprang, then the stream hurrying its hoard

of news woke up the valley. Winifred

drew pilgrims limping, eager to be whole.

He signed up slaves of cotton, copper, lead.

Her stream, severed by water wheels, rolled

machines. When Winifred spread her arms wide

to make from shadows trees, he cut them down

but she thinned the Dee channel. Its quayside

became silent, the valley a ghost town.

Now buildings sprawl headless. All around,

sprung green, half-buried: still misshapen ground.

*

Not just the Church preferred its blessings high.

This cotton mill snatched six storeys of sky

with stone from the nearby abbey’s shell

then, power untapped, St. Winifred’s Well.

An act of God, a world in seventy days.

High too squire Pennant’s recorded praise:

all the workers flourished, dined on meat,

fish, “in commodious houses”. Work was sweet.

Poet Jones of Llanasa, muffled voice

of the backwater – why couldn’t he rejoice?

“Rods doom’d to bruise in barb’rous dens of noise

the tender forms of orphan girls and boys.”

Poets. They build nothing. Just hover, stare,

write maudlin history. Except he’d worked there.

*

Ingenuity flowers in such fumes.

New copper bolts were roots helping great ships

spread wide. Brass beakers moistening the lips

of Africa, exchanged for slaves, seemed blooms.

Up there, notice, a fly-wheel gouged the wall.

In this bank, too, an opening faced with brick

like an oven gone drowsily rustic;

no grass, webs or wormcasts though. Earth, that’s all

almost. Hereabouts being where the knack

of refining human brushes took hold –

twigs bound in rags who carefuly swept back

arsenic from this flue and lived to rot –

last year they found a skull, some ten-year-old

ingenuity planted then forgot.

*

The wall keeps on haemorraging dark green

through the bricked-up centuries, through soil

Meadow Mill injected with copper spoil.

And its damp spillway is coloured gangrene

in memory of times, as Pennant said,

when workers obeyed the “antient law”

of sluicing thoroughly before meals or

watched “eruptions of a green colour” spread.

(They knew dogs, if they licked the sheeting, slept

for good.) So justice as well, urbane,

copper-bottomed, is remembered here. Yet

though the wall’s washed scrupulously by rain,

strange that metal still heaves through. Dogs drop.

It has tasted men and starves and cannot stop.

*

For three years, Frederick Rolfe alias

Baron Corvo, the Crow, pecked at the shell

of Holywell. He saw in it himself,

more idea than place, a proud man mostly

beak who squabbled, wrote and painted, furious

with “Sewer’s End”, obscurity’s rebel

till fury grew him wings. Two crows he left

in painted banners still caw “Look at me!”

Flashing, art’s narrowed gaze will open

on polluted water and turn even stones

to mirrors. The Well running wheels ran men.

Its stream’s “uproll and downcarol” Manley

Hopkins sang rang walls from where Poet Jones,

apprenticed to heartache, jumped to sea.

*

Ice tore a trench to the estuary.

Grass healed its sides. Water devised a well.

An idea, grown around it like a tree

surviving as an arched stone spell,

towered so pilgrims are still beckoned here,

a welling of belief that named a town.

When another idea for water

bricked up the flow, its weight wore people down.

The centuries keep waking to change dreams.

Dug from the undergrowth: brickwork’s feud

with stone for possession of the stream.

And voices insisting water is alive –

those pursuing always and, pursued,

those in need of miracles to survive.

We took a break from lunch and I was shown around the house and garden. There were birds carved by John and painted by Marilyn, and artworks in various media created by Marilyn, especially ceramics.

Outside, under a tree was a little sculpture garden.

Unlike John, who comes from Cymmer Afan in South Wales and does not speak Welsh, Marilyn comes from Pwllheli in the north-western heartland of the Welsh language, and spent her career teaching in Welsh-medium schools. She did not seem to push her own creations forward, though we were surrounded by them, but indicated that she had been a lifelong maker of art objects. John was more specific. When he was eleven there had been a school eisteddfod, he was encouraged to contribute some poetry and was hooked, haunting the school magazine with his poems, and continuing through a long teaching career, notably as head of English at Prestatyn High School. Important too were some sabbaticals he spent teaching creative writing at universities in the United States, in Michigan, Washington and Utah: alongside the poems about Deeside, the North Wales coast and the wider Welsh scene, his books have many poems derived from his experiences in America, contrasting but clearly linked with his depiction of Wales: there are miners, displaced first nations, powerful religion and a host of sharply-drawn characters, some of them carvers of birds in wood.

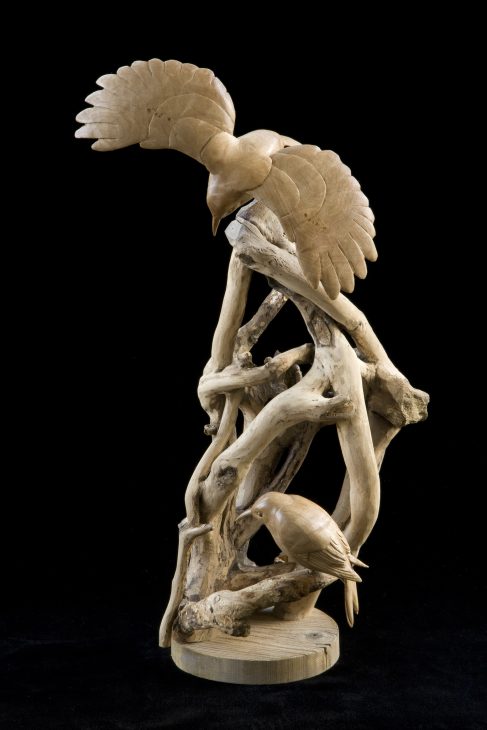

While John could pinpoint the origin of his involvement in poetry, the origin of his interest in woodcarving, and especially in carving birds, seemed less clear, but grew somehow out of a childhood love of making things like Airfix model aircraft. He recalled his mother questioning whether it was worth doing, a discouragement which nonetheless spurred him on. The skill did not come easily, perhaps in contrast to his facility for writing, but the carving of birds in wood ran alongside and perhaps behind his writing of poetry throughout his adult life, and was given a big push by his contact with others who carved birds in wood in the United States. He talks about the process at length in his most recent book, Bird River (Carreg Gwalch, 2023), from which most of the illustrations of bird carvings in the present feature are taken. The book is an absorbing mix of encounters related to the carving of birds, descriptions of the creative process, discussion of influences, poems, and photographs. The title points to the amount of time John spends walking the banks of the nearby river, the Clwyd, collecting driftwood for the mounts which have become such a feature of the carvings. As we spoke, he suddenly interjected that he loves collecting the driftwood and putting it together with the birds. Really, he told me, the driftwood has become the main event, a sort of gift that appears twice, first when he finds it, and again when he opens up the store in which it has been left to dry. He felt so thankful for it.

As in the poetry collections, Bird River contains a good deal of humour:

Then there was the small tribe of young men living by the Clwyd for about four months last summer, on a muddy creek at Rhyl. Some lived in a sod hut they’d built, flying a Welsh flag. Some lived in tents. Nearby was a handsome structure made of driftwood and a large bakery tray. By the time I encountered them, they were shooting rabbits and fishing but had decided not to kill pheasants because it was the breeding season. They were jobless. A lot of the money saved on accommodation went on drinking in the scenery. And they left behind, filling two burned-out cars already there when they’d arrived, hundreds of beer cans shining silver against the rust-brown like an Arts Council installation. I admired their enterprise, living, as one of them put it, ‘the rock ’n’ roll lifestyle’. So when later one of them checked out my armful of wood and driftwood-collecting costume and asked, ‘Sleeping rough, are you?’, I felt oddly flattered.

John carves the birds and they are then coloured by Marilyn:

Once John has finished the carving, it’s usually over to me. The first stage is to use a pyrography tool to produce the texture of the feathers… A low temperature will produce a light mark and hundreds of these barbs are required to give the bird a feathery look. At a high temperature, the tool can also be used to produce dark brown markings. Sometimes, with a bird such as a curlew, which is basically white and brown, white paint or dye and the use of pyrography is all that is required. Compared with a paintbrush, even a very fine one, it’s more accurate. But most birds will be painted. Many British birds are what birders call ‘little brown jobs’, so achieving shades of brown and grey is vital. The colours I use most are earth tones: Raw Umber, Burnt Umber, Raw Sienna, Burnt Sienna, and White.

(Marilyn Davies, quoted in Bird River)

My tour of the Davies’ house and garden concluded in John’s workshop.

Surrounded by tools, partly fashioned carvings and driftwood pieces waiting for use, it was the tactile nature of it all that struck me. I asked John if carving the birds had replaced writing poetry. He was emphatic: yes, that was right. How did that happen? Again he was quite direct: he had found that he was writing rubbish, and it was embarrassing when editors who had once eagerly accepted his work now sent it back with a more or less polite rejection. He thought that poets commonly ran out of steam as they got older: the reactiveness that fires the images becomes less, one is not so much moved by events. I asked him if the tactile nature of carving and the fact that driftwood is a found object – a gift, as he put it – helped him to get the artwork going. He seemed to think that this was right. He was so grateful, he said, that the carving was there when his poetry gave out. It was the second time in our conversation that he spoke of his gratitude for what this form had given him.

In Bird River, John adapts a poem from Flight Patterns which ties together his preoccupations with woodcarving, birds and the environment of the estuary. This is Decoys. It takes the form of a dialogue between the poet and the Parkgate wildfowler Harold Gill. Gill was and remains a somewhat legendary figure in his locality, one of the last people to earn his living by wildfowling in the Dee estuary, and certainly the only one to record much about the life, in a remarkable memoir Dee Wildfowler: the last professional (1982), edited and published by Leslie Brockbank. Here is the complete original version of the poem.

Decoys

(in memory of Harold Gill)

My timber for carving’s from the shore,

driftlumps water sluices out

so it dries fast and won’t crack. Elm most of all.

Bones in the woodshed’s drought,

they clench. Opened months later, a store

of ripeness surprised is the windfall.

We’d leave for Mostyn, cross

the Shrouds. You had to know the water.

What use is a duck-punt once a week?

You’re not informed. Birds on the ebb won’t stir,

just sit there packed. The flood brings chaos.

High tide meant hide-and-seek.

I carve birds, ducks often: pintail

and mallard, a teal, shapes wood lays for the hand.

Bandsaw for roughing out — check the grain

runs with the bill. Chisels, rasp. Elm is hard sand.

With oil or polish, what’s been fingered stale,

another late surprise, is sunburnt terrain.

Each day — start early. We liked a NE

in the face when we picked our spot:

no wobblings, steady as she… Sixty yards

for a clean kill. 20 ounces. AA shot.

But for food, I wouldn’t have killed — at least

not birds. Smooth the feathers, keep no scorecard.

Best I like the curve where crown, cheek,

sweep down through the swell of chest,

the sweptback, cleared-for-action prow

of a poised gathering unrest

that, from the moment’s peak,

though wood, might just take off, go anyhow.

It wasn’t the birds mainly,

that’s something I can’t nail.

One chap I took, a February morning,

sang for hours — threats to shoot him failed.

Never sung before. The estuary

was fine, I lived on dusk and dawn.

Beyond wood: an airy something

from nothing wood’s a pretext for.

Alone at last with the whole mind’s scope,

you drift. Almost a familiar shore.

Stirrings, gleams are stalked, and springing

this time they are yours, you hope.

Not that bird carving is entirely without drawbacks. John told me that it was hard to find others working in the same field locally, or even further afield. In the United States he appears to have found a vigorous community of fellow carvers of birds, leading to various escapades which find their way into the poems; but not in the UK. He thought that this might be because of the time the work takes: he recalled a woodworker at a craft fair who had “Bloody Ages” printed on the back of his jacket, in answer to the question which is always asked. But John said that the slowness of the work did not bother him: it was the whole process, not so much the end product, which was engaging.

As I made my goodbyes, the Davies’ thanked me for taking an interest in their work, as if few people noticed it. I confessed myself baffled: there is so much there to take an interest in. I hope you have enjoyed reading about their art in this edition of Between Rivers. If you would like to find out more about their carvings of birds you can visit their website, Birds In The Wood, or visit their Facebook page.

BETWEEN RIVERS is a quarterly series edited by Alan Horne. It is focused on the area bounded by the rivers Alun, Dee and Gowy, on the border between England and Wales in Flintshire, Denbighshire and Cheshire. You can read about the background to Between Rivers in the Introduction